💙Identifying Critical but Underrepresented Ocean Regions and Ecosystems

The health and resilience of the global ocean are fundamental to planetary well-being, supporting a vast array of life, regulating climate, and providing essential resources for human societies. Despite its critical importance, significant portions of the ocean remain understudied and underrepresented in conservation efforts, potentially leading to irreversible losses of biodiversity and ecosystem function.

This article undertakes a comprehensive analysis to identify specific ocean regions and ecosystems that are currently receiving insufficient attention or resources, examining the reasons behind this underrepresentation and the potential consequences for marine conservation and global sustainability.

Defining Underrepresented Ocean Regions and Ecosystems

“Underrepresented” refers to regions or ecosystems that receive disproportionately less attention or resources compared to their ecological, functional, or socio-economic importance and the threats they face. This underrepresentation can manifest in several ways.

- Limited scientific data is a key indicator of underrepresentation.

- Insufficient monitoring efforts further exacerbate this issue, hindering our ability to detect changes and assess the health of these critical areas.

- The vastness and depth of the ocean, particularly the deep sea, inherently contribute to the challenges in data collection, leaving these environments largely unexplored and their roles in the global ocean system poorly understood.

- Even in more accessible regions, certain marine invertebrates and microorganisms often receive less research attention compared to more charismatic megafauna, leading to significant gaps in our understanding of ecosystem functioning

- Many critical ocean regions lack sufficient protected areas, leaving them vulnerable to various threats. Furthermore, even when protected areas are established, they often suffer from insufficient management, funding, and enforcement, resulting in limited effectiveness.

- Limited public and policy focus contributes to underrepresentation. This lack of visibility can lead to lower prioritization in research agendas and funding allocations, perpetuating a cycle of neglect.

- The “out of sight, out of mind” phenomenon often leads to the underfunding and lack of attention towards critical ocean areas, particularly those located far from human populations. Despite the ocean’s fundamental role in climate regulation and supporting life, ocean conservation receives a disproportionately small share of global research funding compared to other scientific disciplines

Understudied and Underfunded Ocean Regions

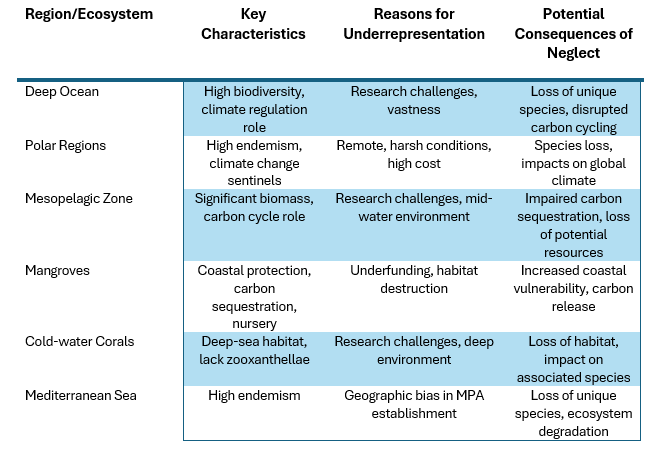

Several key ocean regions stand out as being both critical and underrepresented in research and conservation efforts.

The Deep Ocean:

- This vast realm, encompassing the waters and seafloor below 200 meters, constitutes over 95% of Earth’s living space and harbors a remarkable diversity of habitats and organisms. Our understanding of deep-sea ecosystems remains limited due to the inherent challenges of exploration and research in these extreme environments. The deep ocean serves as the largest carbon reservoir on the planet, absorbing a significant portion of anthropogenic CO₂ and heat, yet the impact of emerging threats like deep-sea mining on these critical functions is poorly understood. The increasing interest in exploiting deep-sea resources for minerals poses a significant threat to these fragile and largely unknown ecosystems, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive research and robust regulatory frameworks before irreversible damage occurs.

Polar Regions (Arctic and Southern Ocean):

- The Arctic and Southern Oceans are home to unique cold-adapted species and play a pivotal role in the global climate system. The Southern Ocean, in particular, harbors approximately 10,000 endemic species, highlighting its unique biodiversity. These regions are experiencing rapid and dramatic environmental changes, including accelerated warming, extensive sea ice loss, and increasing ocean acidification.

- The Antarctic Peninsula, for instance, is among the fastest-warming areas on Earth, leading to significant ice loss. However, conducting research in these remote and harsh environments presents significant logistical challenges and high costs, contributing to their underrepresentation in scientific studies and hindering our ability to effectively monitor and understand the ongoing transformations

Mesopelagic Zone (Twilight Zone):

- Situated between 200 and 1000 meters deep, the mesopelagic zone represents approximately 20% of the global ocean and holds significant ecological value. Despite its ecological importance, the mesopelagic zone remains relatively understudied due to the challenges of investigating this mid-water environment. This zone is characterized by low light conditions and the presence of oxygen minimum zones (OMZs), areas with significantly reduced oxygen concentrations. Alarmingly, these OMZs are expanding rapidly due to rising ocean water temperatures, posing a significant threat to oxygen-dependent marine life and representing an underreported impact of climate change.

Ocean Surface Ecosystems:

- The ocean surface, covering 72% of the Earth’s total surface, provides habitat for unique neutronic communities and distinct ecoregions found at specific latitudes and ocean basins. However, the ocean surface is also at the forefront of climate change and pollution, facing direct impacts from rising temperatures and the accumulation of plastic, oil slicks, chemical spills and other debris. High concentrations of neutronic life are found within the plastic-rich North Pacific Garbage Patch, highlighting the direct impact of plastic pollution on these surface communities and the marine life that depends on them, a consequence that remains understudied. Same applies to the other pollutants.

Portal areas

Maritime ports are the heartbeat of global trade, moving 80% of the world’s goods and connecting continents through a vast and dynamic logistics network. The increasing scale of port activities and their proximity to sensitive coastal ecosystems have raised significant concerns about their environmental impact, particularly on biodiversity and the planet’s climate system. Many ports are in ecologically rich coastal and estuarine zones – areas that serve as breeding, feeding, and nursery grounds for marine life. However, the development and day-to-day operation of these ports pose serious risks:

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Maritime shipping and port operations contribute nearly 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, primarily CO2, NOx, SOx, and particulate matter.

- Habitat destruction: Port infrastructure and expansion often destroy coastal ecosystems like mangroves, wetlands, and coral reef. Dredging alters seabed dynamics, affecting marine biodiversity and sediment flows

- Water Pollution from vessel traffic, including oil spills, chemical discharges, , heavy metals, plastics and noise, along with industrial activities within the port. Activities through dredging and hull cleaning release sediments and contaminants, such as copper, into waterways.

- Non-native organisms introduced via ballast water.

Specific Geographic Areas:

- The Southern and Eastern Mediterranean Sea, for instance, are ecologically distinctive and exhibit high rates of endemism but have a disproportionately low number of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) compared to the northern part of the basin, indicating a geographic bias in conservation efforts.

- An AI model identified 119 new ocean biodiversity hotspots in the Western Indian Ocean, most of which currently lack protection, suggesting a significant underrepresentation of critical areas in existing conservation strategies.

- The Salas y Gómez Ridge in the Southeast Pacific harbors high levels of marine endemism, yet much of it lies in the high seas, outside of any country’s jurisdiction, and remains understudied, requiring international cooperation for its protection.

- Finally, Gulf of California, a known marine biodiversity hotspot, has revealed a much higher level of biodiversity than previously documented through traditional visual surveys and historical records, indicating that conventional methods may be underrepresenting certain taxa even in well-regarded hotspots.

Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems (VMEs):

- Arctic hydrothermal vents host distinct communities not found elsewhere. These ecosystems are particularly threatened by the emerging deep-sea mining industry, highlighting the urgent need for their protection and further scientific investigation.

- Cold-water corals, found in deeper and colder oceanic waters and lacking zooxanthellae, provide essential habitat and are vulnerable to the increasing threat of ocean acidification.

- Sponge grounds, often associated with commercially important fish populations, are fragile and susceptible to damage from bottom fishing gear, emphasizing the need for effective spatial management.

Coastal Ecosystems:

- Mangrove forests, found in tropical and subtropical coastal areas, are extremely productive, connect terrestrial and marine environments, protect coastlines from erosion and storms, serve as critical nursery areas for many marine species, and are highly effective at sequestering carbon dioxide.

- Despite their crucial role in climate change mitigation and adaptation, mangroves receive only about 1% of global climate finance, indicating a severe underfunding issue.

- Seagrass beds, another vital coastal ecosystem, provide food and shelter for a wide array of marine life, stabilize sediments, improve water quality, produce oxygen, and act as important nursery habitats.1 These underwater meadows are vulnerable to human disturbances, and their loss can lead to increased carbon emissions.

- Salt marshes are also extremely productive ecosystems that provide essential services for many fishery species and protect shorelines from erosion and flooding.

Ecosystems with High Endemism:

- The Mediterranean Sea stands out as a marine biodiversity hotspot with high rates of endemism, ranging from 20 to 30%.

- However, deep-sea habitats and the southern and eastern coastal sites within the Mediterranean are underrepresented in the current network of MPAs, highlighting a gap in conservation efforts.

- Marine caves in the Mediterranean have been identified as important reservoirs of sponge biodiversity, further emphasizing the unique ecological value of this region.

- Coral reefs in the Ryukyu Islands of Japan are another example of ecosystems with high levels of both biodiversity and endemism, facing significant anthropogenic threats. Research in this region shows a bias towards certain taxa and sub-regions, suggesting that the full extent of its biodiversity and the threats it faces may be underreported.

Neglected Habitats:

- Sandy bottom habitats, often perceived as less biodiverse, support a wide array of marine life, including microorganisms, various invertebrates like crabs and clams, and serve as important areas for nesting birds and sea turtles.

- Sargassum mats, floating algae found in the open ocean, provide essential habitat, food, and breeding grounds for a diverse array of marine life, acting as oases in the pelagic environment.

Consequences of Underrepresentation

The underrepresentation of critical ocean regions and ecosystems in research and conservation efforts carries significant negative consequences for marine biodiversity, ecosystem function, and human well-being.2 Neglecting these vital areas can lead to the irreversible loss of unique species and the degradation of essential habitats, ultimately diminishing overall marine biodiversity and the intricate functioning of ocean ecosystems.

Furthermore, underrepresenting regions and ecosystems that play a crucial role in carbon sequestration, such as the deep ocean and mangrove forests, can significantly impair the ocean’s capacity to regulate climate change.1 The ocean’s vital function as a natural buffer against rising atmospheric CO₂ is compromised when key carbon sinks are neglected or degraded.2

The consequences extend to human societies as well. Neglecting ecosystems that support fisheries and provide coastal protection directly threatens the food security and livelihoods of millions of people who depend on these resources.1 The health of the ocean is inextricably linked to human well-being, and the degradation of critical areas can have devastating socio-economic impacts.2

Finally, the lack of data and understanding about underrepresented regions and ecosystems significantly hinders the development of effective marine spatial planning and conservation strategies.9 Informed decision-making for conservation relies on comprehensive knowledge of the areas we aim to protect, and without sufficient data on underrepresented regions, our efforts may be misdirected or ineffective.9

Recommendations for Addressing Underrepresentation

Addressing the underrepresentation of critical ocean regions and ecosystems requires a concerted and multi-faceted approach.

- Increased investment in both basic and applied research is essential to fill the significant knowledge gaps that exist in underexplored regions such as the deep ocean and polar areas, as well as in neglected ecosystems and taxonomic groups. Targeted research initiatives can provide the foundational knowledge necessary for developing effective conservation strategies and management plans.4

- Funding organizations should strategically allocate resources to address the identified disparities, prioritizing investments in underrepresented critical areas and thematic research areas, such as the impacts of salinity changes, oil slicks, ports ballast water and noise pollution, to ensure a more balanced and comprehensive approach to ocean conservation.

- The development of comprehensive monitoring and assessment programs is also crucial for tracking changes in underrepresented regions and ecosystems, evaluating the impacts of various stressors, and assessing the effectiveness of conservation interventions over time. Robust monitoring provides the essential data necessary for adaptive management and informed decision-making in the face of rapid environmental change.

Enhancing international collaboration in research, monitoring, and conservation efforts is vital for addressing the global challenges of ocean conservation, particularly in underrepresented regions. Improved sharing of data and knowledge across different regions and research communities will foster a more coordinated and effective global response.

Finally, raising public awareness and increasing media coverage of underrepresented critical ocean regions and ecosystems can help garner greater support for their conservation and influence policy decisions at local, national, and international levels. Increased public support and political will are often essential for driving meaningful change in conservation policy and funding priorities.

Conclusion

The analysis presented in this report underscores the critical need to address the underrepresentation of specific ocean regions and ecosystems in both research and conservation efforts. Areas such as the deep ocean, polar regions, the mesopelagic zone, portal area and certain coastal and high-endemism ecosystems, along with understudied impacts like salinity and noise pollution, and biases in research focus, require greater attention and resources. The consequences of neglecting these vital components of the marine environment are far-reaching, potentially leading to significant biodiversity loss, impaired climate regulation, threats to food security, and challenges in effective ocean management. By prioritizing research, strategically allocating funding, developing comprehensive monitoring programs, enhancing international collaboration, integrating local knowledge, and improving public awareness, we can move towards a more equitable and effective approach to ocean conservation that safeguards these critical but currently underrepresented areas for future generations.

Leave a comment