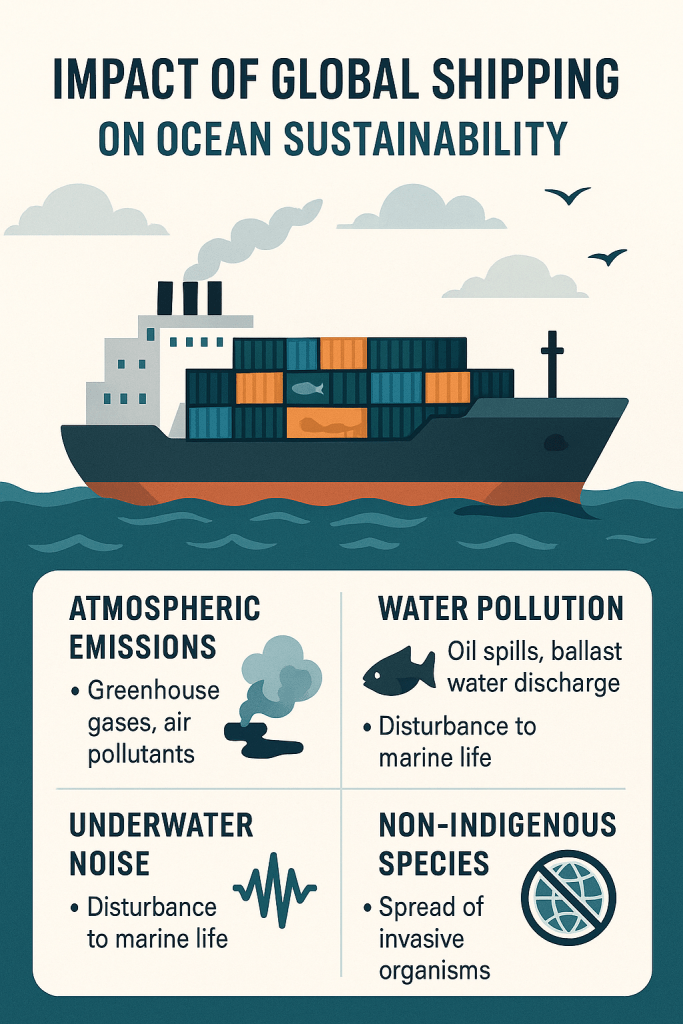

The global shipping industry, while indispensable for international trade, exerts significant environmental pressures on ocean ecosystems. These pressures manifest in various forms, including atmospheric and water pollution, underwater noise, and the introduction of non-indigenous species. Amidst increasing scrutiny on fuel consumption and a drive towards reducing operational costs and environmental footprints, the industry is exploring mitigation strategies such as slow steaming and the adoption of wind-assisted propulsion. This report underscores that hull fouling and poor ship conditions play a particularly detrimental role in exacerbating environmental damage and increasing fuel consumption.

Diverse Environmental Pressures Exerted by Maritime Transportation

Atmospheric Pollution

The global shipping industry relies heavily on the combustion of fossil fuels, primarily heavy fuel oil (HFO) and marine gas oil (MGO), for the propulsion of vessels and the generation of onboard power. This dependence results in the emission of significant quantities of greenhouse gases (GHGs), including carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), which contribute to global climate change. Projections indicate that if current trends persist without substantial intervention, shipping emissions could escalate by as much as 130% of 2008 levels by 2050, posing a severe threat to achieving global climate goals. Recognizing the urgency, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has set ambitious targets for GHG emission reduction, aiming for net-zero emissions from international shipping by or around 2050.

Beyond GHGs, ships also release other harmful air pollutants, including sulfur oxides (SOx) and nitrogen oxides (NOx), which have detrimental impacts on local air quality, human health, and contribute to the formation of acid rain. Notably, the fuel utilized in large marine vessels is often significantly more polluting than road diesel, leading to substantial public health damage in port and coastal communities. While regulations have been implemented to reduce sulfur emissions from ships, these measures have been linked to an unintended consequence: a potential increase in global temperatures due to a reduction in the cooling effect of sulfate aerosols.

Another significant concern is the emission of black carbon, particularly from the combustion of heavy fuel oil in ship engines.

Ocean Water Pollution

Accidental oil spills, resulting from groundings, shipwrecks, bunkering accidents, or other activities, release crude oil and other petroleum products into sensitive marine habitats, causing immediate and long-term damage. Historical examples, such as the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico and the Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska, highlight the devastating consequences for marine mammals, seabirds, sea turtles, fish, and coastal ecosystems.

Routine ship operations generate a wide range of pollutants that can cause both immediate and long-term environmental damage. These include garbage, scrubber effluent, sewage (black water), greywater, chemical waste, and sludge. The international shipping industry is estimated to dump over 250 million gallons of grey and black water into the sea each day.

Furthermore, deliberate illegal dumping of oily residues from routine operations accounts for a staggering 90% of all oil discharged by ships.

Anti-fouling paints, used to prevent marine organisms from attaching to ship hulls, contain toxic compounds (biocides) that leach into the marine environment, harming a variety of species.

It is estimated that ships can be responsible for anywhere between 20% and 70% of plastic pollution in the oceans, depending on the region. This pollution arises from cargo losses, illegal dumping of plastic waste, and improper waste management during routine operations. The loss of containers from ships due to various factors, including extreme weather and improper securing, further exacerbates the problem of marine plastic pollution, with millions of tons of cargo potentially lost at sea annually.

Underwater Noise Pollution

Cargo vessels, in particular, produce low-frequency sounds that can travel hundreds of kilometers underwater. This increasing ambient noise is less popular and hard to measure but has significant detrimental effects on marine life, which relies on sound for essential activities such as communication, navigation, finding food, and avoiding predators. Elevated noise levels can disrupt these vital behaviors. In some cases, marine animals may be forced to move away from their preferred habitats or deviate from their migratory paths to avoid noisy areas.

Introduction of Non-Indigenous Species

Ships act as major vectors for the introduction of non-indigenous species (NIS) into new marine environments, primarily through ballast water and biofouling. Ballast water, taken on by ships for stability, can contain a vast array of marine organisms, including bacteria, microbes, small invertebrates, eggs, cysts, and larvae of various species, which are then transported across the globe. Similarly, biofouling, the accumulation of microorganisms, plants, algae, and small animals on ships’ hulls and other submerged surfaces, provides another significant pathway for the transfer of invasive aquatic species (IAS).

Examples of invasive species introduced via ballast water include zebra mussels, which have caused billions of dollars in damage to infrastructure in the Great Lakes.

Physical Impacts and Habitat Disruption

Beyond the various forms of pollution, the shipping industry also has direct physical impacts on marine habitats. The construction of new port infrastructure can lead to the destruction of sensitive seafloor habitats. In Arctic regions, the passage of icebreakers can damage the habitats relied upon by seals, walruses, and polar bears.

Current Strategies for Mitigating Shipping’s Impact

Slowing Down (Slow Steaming)

Slow steaming, the practice of reducing the operational speed of ships, has emerged as a significant strategy for mitigating the environmental impact of shipping. While slow steaming offers considerable advantages, it can lead to longer voyage times, potentially requiring shipping companies to deploy more vessels to maintain the same cargo capacity.

Despite this, several major shipping companies have successfully implemented slow steaming practices since the 2000s, demonstrating its feasibility and cost-effectiveness.

Wind-Assisted Propulsion

Wind-assisted propulsion systems (WAPS) are back on trend and are experiencing a resurgence in the maritime industry as a promising technology for reducing fuel consumption and emissions. These systems harness the power of wind to supplement the main engine propulsion of a vessel, thereby reducing its reliance on fossil fuels.

To maximize the efficiency of wind-assisted ships, the integration of wind real-time conditions, advanced weather routing and digital technologies is crucial to take advantage of prevailing wind conditions. This makes the technology still hard to measure its efficiency.

Other Technological and Operational Improvements

In addition to slow steaming and wind-assisted propulsion, the shipping industry is exploring a range of other technological and operational improvements to enhance ocean sustainability. The development and adoption of alternative fuels with lower or zero carbon emissions, such as liquefied natural gas (LNG), methanol, ammonia, and hydrogen, are gaining traction as long-term solutions for decarbonization. Advancements in ship engine design and the implementation of various energy-efficient technologies also contribute to reducing fuel consumption. Furthermore, the mandatory implementation of ballast water treatment systems on ships is crucial for preventing the spread of invasive aquatic species.

Regulatory Frameworks and Industry Initiatives

Addressing the environmental impact of shipping requires a robust regulatory framework and proactive industry initiatives.

International regulations, primarily established by the IMO, play a vital role in setting standards for GHG emissions reduction, ballast water management, and other environmental concerns.

Regional initiatives, such as the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) for shipping, further contribute to driving down emissions within specific geographical areas.

Additionally, various industry-led efforts and collaborations are underway to promote the adoption of sustainable shipping practices and accelerate the transition towards a greener maritime sector.

Recommendations

Strengthen and expand international and regional regulations aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution from the shipping sector, with clear targets and timelines aligned with global climate goals.

Support and fund research initiatives focused on understanding the impacts of shipping on marine ecosystems and developing effective mitigation strategies.

Establish and enforce stricter regulations on the discharge of all forms of pollution from ships, including operational discharges and waste management.

Enhance monitoring and enforcement mechanisms to ensure compliance with environmental regulations within the shipping industry.

Promote international collaboration and information sharing on best practices and innovative solutions for sustainable shipping.

Develop improved methods for monitoring, tracking, and mitigating plastic pollution originating from ships and maritime activities.

Assess the scalability, sustainability, and environmental lifecycle impacts of various alternative fuels for the shipping industry to inform policy and investment decisions.

Conclusion

The global shipping industry exerts significant and multifaceted pressures on ocean sustainability, encompassing atmospheric and water pollution, underwater noise, and the introduction of non-indigenous species.

Continued efforts in technological innovation, the adoption of alternative fuels, and the strengthening of regulatory frameworks are crucial for achieving a greener maritime industry and safeguarding the health of our oceans for future generations.

Leave a comment