🐟Overfishing, defined as the capture of fish faster than populations can replenish, represents one of the most critical threats to marine ecosystems worldwide. It leads to the depletion of fish stocks, disrupts delicate food webs, and ultimately contributes to the collapse of marine biodiversity.

Global Status and Trends in Fish Stocks

Recent assessments reveal a concerning trajectory for global fish stocks. For the first time in history, farmed seafood production has surpassed wild capture, yet overfishing of wild fish stocks continues to increase, and the number of sustainably fished stocks is declining.

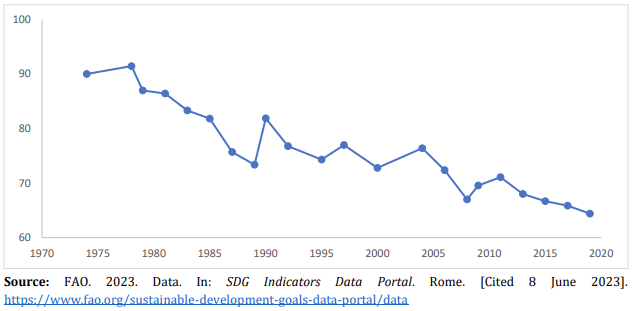

The proportion of sustainably fished marine fish stocks fell to 62% since the 2022 Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report, marking a striking long-term decline from 90% in the 1970s.

Conversely, the percentage of stocks defined as “overfished” rose to 38% in 2024, up from 35% in 2022. Another report indicates that 37.7% of the world’s monitored marine fish stocks were overfished in 2021, an increase of 2.3 percentage points from 2019, continuing a multi-decade trend.

In 2019, 35.4% of global stocks were overfished, a significant increase from 10% in 1974.

A closer examination of these statistics reveals a nuanced picture regarding seafood production and wild stock health. While aquaculture production is growing rapidly (6.6% since 2020, projected 17% by 2032) and now accounts for 51% of global aquatic animal production, this growth has not alleviated the pressure on wild populations. This suggests that while overall seafood production is increasing, the underlying issue of wild stock depletion persists and is worsening. Furthermore, data indicates that larger, commercially important stocks are more frequently fished within biologically sustainable limits compared to smaller stocks, as evidenced by the disparity between weighted (76.9%) and unweighted (62.3%) percentages of sustainably fished stocks. This implies that while economically significant fisheries may receive more management attention, the overall health of the diverse range of global fish stocks is deteriorating.

Regional disparities in overfishing are stark:

- The Mediterranean and Black Sea consistently exhibit the highest percentages of overfished stocks, with 62.2% in 2015 and 63.3% in 2017, and are frequently cited as the world’s most overfished seas.

- The Southeast Pacific also faces severe overfishing, with 66.7% of its stocks at biologically unsustainable levels in 2017.

These persistent regional vulnerabilities underscore that while the global rate of decline in fish stocks may have slowed recently , severe localized crises demand targeted interventions.

In contrast, certain regions like the Eastern Central Pacific and Southwest Pacific have lower proportions of unsustainable stocks (13-21%). Notably, the management of commercial tuna stocks shows relative progress, with 87% fished sustainably in 2021, and 99% of the total catch coming from sustainably managed stocks.

This success, however, is not universal, as specific species such as bluefin and albacore tuna stocks remain overfished.

Ecological and Socio-Economic Consequences

The consequences of overfishing extend far beyond the immediate depletion of target species. Destructive fishing practices, such as bottom trawling, act like “ocean bulldozers,” causing significant damage to benthic habitats crucial for the survival and reproduction of many marine species. This physical disruption reduces habitat complexity, leading to a decrease in species richness and overall biodiversity. For example, Mediterranean seagrass beds, vital nursery grounds for many fish species, have already disappeared in some areas due to bottom trawling. The high bycatch rates associated with industrial trawling, where undersized hake and red mullet can constitute up to 60% of the catch in the Mediterranean, prevent these fish from reaching maturity and reproducing, further damaging populations.

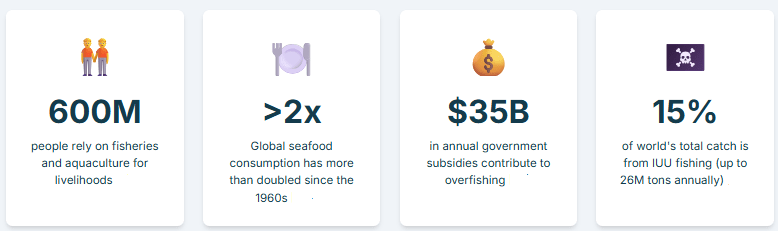

Socio-economically, overfishing undermines the livelihoods and food security of millions globally. An estimated 600 million people rely, at least partially, on small-scale fisheries and aquaculture for their sustenance and income.

- Small-scale fisheries alone account for 90% of employment in fisheries worldwide, supporting almost half a billion people, 97% of whom live in developing countries and often face high levels of poverty.

- The decline in fish stocks and subsequent reduction in fishery revenues directly impact the economic stability of these coastal communities.

- For instance, in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, the contribution of sustainable fisheries to GDP fell from 1.06% in 2011 to 0.80% in 2019 due to declining stock sustainability in the Pacific Ocean.

This highlights that overfishing is not merely an environmental concern but a significant social justice and development issue, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations and exacerbating poverty and food insecurity in developing coastal nations.

Key Drivers of Overfishing

The escalating problem of overfishing is driven by a complex interplay of factors, such as:

- Increasing global demand for seafood,

- Unsustainable fishing practices,

- Governance failures.

Global seafood consumption has more than doubled since the 1960s, reaching an average of 20.5 kg/person per year, intensifying fishing activities often beyond sustainable limits. This rising demand is met by modern industrial fishing practices, such as large trawlers and advanced sonar systems. While highly efficient, these methods are often indiscriminate, leading to the rapid depletion of target species and significant bycatch rates, with bottom trawling, for instance, resulting in bycatch rates of up to 90%. This technological capacity, combined with the economic pressures faced by many coastal communities (where approximately 200 million people are directly or indirectly employed by the fishing industry), creates a powerful incentive structure for unsustainable exploitation.

Furthermore, government subsidies for fishing industries, estimated at around $35 billion annually, inadvertently encourage overfishing by making economically unviable practices profitable, thereby contributing to overcapacity in fishing fleets.

A significant portion of overfishing also stems from illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, which accounts for an estimated 15% of the world’s total catch, or up to 26 million tons of fish annually. This “invisible” overfishing undermines all other conservation efforts, as it operates outside of established management frameworks, making it exceedingly difficult to track and control.

Compounding this issue are weak regulatory frameworks, inadequate control measures, and insufficient enforcement in many regions. Globally, 73% of fish stocks are subject to no scientific assessment or management. This pervasive lack of comprehensive data and effective governance means that a vast amount of fishing activity proceeds without proper oversight, preventing the establishment of accurate baselines for recovery and hindering the implementation of sustainable practices.

Policy response

At the international level, significant progress has been made with the adoption of the legally binding Agreement on Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement) in 2023. This agreement covers almost two-thirds of the total ocean surface area and provides a legal foundation for designating marine protected areas (MPAs), which can help limit problematic practices like overfishing.

As of 2021, MPAs covered 8% of global coastal waters and oceans, moving closer to the 10% target called for in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

However, a substantial gap remains, as more than half (55%) of marine Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) are still not safeguarded.

Another crucial international development is the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement on harmful fishing subsidies, which targets payments contributing to IUU fishing and overfished stocks. While a significant step, this agreement still requires ratification from 22 more countries to take effect, highlighting the ongoing challenge of translating international consensus into widespread implementation.

Technological innovations are playing an increasingly vital role in supporting sustainable fisheries management. Remote sensing technologies, including satellite imagery and aerial drones, provide unprecedented accuracy for assessing fish stocks and their habitats. Electronic monitoring systems, such as onboard cameras, offer real-time data on catch and bycatch, improving compliance with regulations. Advanced acoustics, including echosounders, are used to estimate fish populations and monitor marine life, while mobile applications and blockchain technology enhance data collection, transparency, and traceability throughout the seafood supply chain.

Despite these advancements, the interplay between overfishing and climate change presents a formidable challenge. Climate change is rapidly altering ocean conditions, making it more difficult for overfished populations to recover by reducing their resilience and shifting their geographic ranges.

This dynamic means that sustainable fisheries management cannot be pursued in isolation require a call for action such as:

- It must be integrated with broader climate action to be truly effective

- Requiring adaptive strategies tailored to local conditions.

- Advanced technology for monitoring and enforcement.

- Strong political will for comprehensive regulatory frameworks that address the root causes of overfishing.

- Adequate funding.

At SaveOCEAN we are fighting against overfishing through:

🔹 Policy advocacy for sustainable fishing laws

🔹 Support for local and indigenous fishing communities

🔹 Campaigns against destructive fishing practices

🔹 Marine conservation programs worldwide

What You Can Do Today:

✅ Join us to stop industrial overfishing

✅ Donate to support on-the-ground ocean defenders

✅ Support small community fishing

✅ Share this message – awareness is the first wave of change

✅ Choose sustainably sourced seafood

💪 Lets celebrate the Ocean. Save our Future

Leave a comment