Oil and chemical spills, while often highly publicized, represent a distinct category of ocean challenge. For decades, the image of a catastrophic oil spill – coastlines choked with black sludge, wildlife struggling to breathe- has haunted our collective memory. These were the disasters that galvanized international regulations and pushed the oil shipping industry to change.

Trends in Spill Frequency and Volume

According to data from the International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation (ITOPF), the number of major oil spills—those exceeding 7 tonnes—has plummeted by over 90% since the 1970s. In 2024, only ten such incidents were recorded worldwide. It’s a remarkable achievement, especially given the steady rise in global oil shipping however these are the spills monitored and detected.

But as we celebrate this progress, a more insidious story unfolds beneath the surface.

Because the biggest threat to our oceans today doesn’t come from the rare, headline-making disaster. It comes from what happens every day, out of sight, and often illegally.

The Oil You Don’t See

While catastrophic spills have become less frequent, a staggering 90% of all oil discharged by ships is attributed to deliberate illegal dumping of oily residues from routine operations, which collectively is thought to discharge much more oil into the oceans each year than the headline-grabbing disasters. This implies that while major accidents are decreasing, widespread, chronic, and often illegal pollution continues to pose a significant cumulative threat. This chronic pollution doesn’t make headlines. It doesn’t trigger emergency response teams. But drop by drop, it’s poisoning our seas at a scale far greater than any single tanker disaster.

We’ve solved the problem of the dramatic. We haven’t yet solved the problem of the systemic.

Beyond Oil: The Silent Spread of Chemicals

And oil isn’t the only threat. Chemical pollution from ships is rising, and it’s largely going unnoticed. Each year, between 9,000 and 20,000 tonnes of hazardous chemicals are accidentally released into the oceans. The U.S. NOAA alone responds to over 150 oil and chemical spill events annually.

But here’s what’s more alarming: under current international regulations- yes, legal standards– millions of liters of hazardous and noxious substances (HNS) can still be discharged during tank-cleaning operations. Tens of thousands of tonnes of solids are also legally dumped into the ocean each year.

These aren’t violations. They’re loopholes.

Individually, each discharge may seem negligible. But collectively, they form a toxic tide—slow-moving, largely invisible, and entirely within the law.

Causes and Geographical Vulnerabilities

Oil and chemical spills don’t always begin with a dramatic explosion or a towering black plume on the horizon. Sometimes, they start quietly: a small human error, a faulty valve, a storm offshore. Other times, the damage is deliberate—a decision made in the dark, out of sight, in violation of laws, ethics, and nature.

From tankers and barges to pipelines and offshore rigs, our industrial web stretches across land and sea. When it fails—through carelessness, technical failure, or natural disaster—the results can be catastrophic. And while technology and regulation have made accidental spills less frequent, a darker problem persists: intentional pollution. Illegal dumping remains stubbornly widespread, driven by weak enforcement, economic convenience, and the gamble that no one is watching.

But someone always pays the price. Our Ocean!

What Happens When Oil Meets Water

The moment oil hits water, the clock begins ticking. How fast it spreads, where it travels, and how deep the damage goes depends on the chemistry of the spill and the character of the water—its temperature, currents, and depth. Most oils float, forming slicks that suffocate marine life and shorelines. But others—like heavy oils or even natural substances like animal fats—can sink, creating hidden toxic zones that endure for years.

And these dangers aren’t limited to coastlines. As the search for oil pushes into more remote, riskier territories—polar regions, salt basins, submerged continental shelves—the chances of spill response delay grow. In these environments, containment isn’t just harder. It’s sometimes nearly impossible.

Geographically, the distribution of oil reserves and transportation routes influences vulnerability. Slightly less than half of the world’s proven oil reserves are located in the Middle East, with other significant reserves in Canada, the United States, Latin America, Africa, and Russia/Kazakhstan. Most petroleum is concentrated in a few large fields, with two-thirds of supergiant fields found in the Arabian-Iranian sedimentary basin.

As easily accessible oil reserves deplete, future exploration and extraction may shift to “frontier basins” located in difficult environments, such as polar regions, beneath salt layers, or within submerged continental margins. This implies increased risks of spills in remote or deep-sea environments where response efforts are inherently more challenging.

Furthermore, while the focus is often on marine spills, oil spilled on land can also reach lakes, rivers, and wetlands, subsequently impacting marine environments, highlighting the need for a comprehensive “source-to-sea” approach to pollution prevention.

One Spill, a Generation of Damage

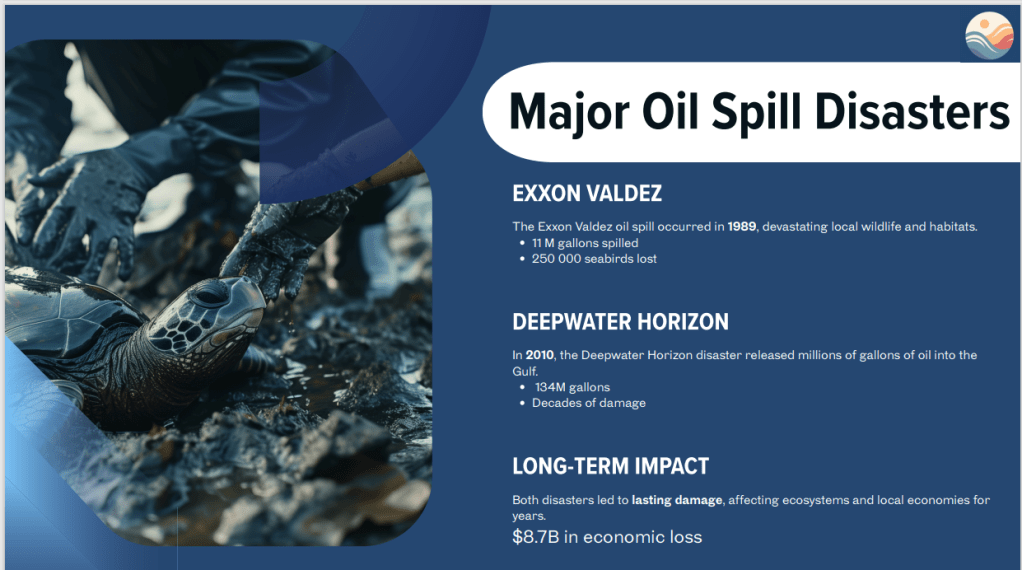

We’ve seen this before. The Exxon Valdez spill in 1989 dumped 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound, blackening over 1,300 miles of pristine shoreline. It killed an estimated 250,000 seabirds, thousands of sea otters and marine mammals, and billions of fish eggs. Decades later, some species still haven’t recovered.

And then there was Deepwater Horizon in 2010, a catastrophe that poured 134 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico over 87 harrowing days. The visible toll was staggering—thousands of dolphins, sea turtles, and birds lost—but the invisible impacts were even worse: reproductive failure, damaged immune systems, and devastated ecosystems that may take more than 20 years to heal.

These are not just tragic stories. They are lessons written in oil across generations.

When Nature Pays the Bill

The environmental cost is heartbreaking. But the economic toll is staggering too.

After Deepwater Horizon, the U.S. economy saw an estimated $8.7 billion in losses—with the fishing industry, local businesses, and communities hit hardest. Shockingly, in many major spills, actual compensation awarded has been just a fraction of what was claimed. The gap between damage done and justice served is not just a legal flaw—it’s a moral failure.

And chemical spills carry their own economic shadow. Contaminated drinking water, forced business closures, mass migration away from affected areas—these ripple effects are long-lasting and disproportionately affect smaller, local communities. The bigger the spill, the harder the recovery—and the greater the gap between those who pollute and those who suffer.

Economically, major spills incur substantial costs. The DWH spill was estimated to result in potential losses over seven years of $3.7 billion in total revenues, $1.9 billion in profits, and $1.2 billion in wages, with a total economic impact of $8.7 billion, disproportionately affecting commercial and recreational fisheries. A critical issue is the significant discrepancy between damage claimed and compensation awarded; for the largest oil spills, final compensation has been nearly 10 times lower than the damage claimed. For instance, the Haven oil spill resulted in $1,604 million in claimed damages but only $178.97 million in compensation. This systemic under compensation means that the true costs of pollution are often externalized, borne by affected communities and the environment rather than fully by polluters. Chemical spills can also cause large-scale drinking water contamination, leading to economic losses and decreased public confidence. Furthermore, major toxic chemical spills have persistent adverse effects on local business activity, disproportionately impacting smaller establishments and leading to increased business concentration, driven by factors like worsening credit frictions and population migration away from affected areas.

Table 4: Major Oil Spills by Volume and Location (Selected Case Studies)

| Spill Name | Year | Location | Spill Size (tonnes) | Key Environmental Impacts | Key Economic Impacts | Recovery Status/Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATLANTIC EMPRESS | 1979 | Off Tobago, West Indies | 287,000 | – | – | – |

| EXXON VALDEZ | 1989 | Prince William Sound, Alaska, USA | 37,000 | Mortality of 250k seabirds, 2.8k sea otters, 300 harbor seals, 250 bald eagles, 22 killer whales, billions of salmon/herring eggs. Long-term impacts on seabirds, sea otters, killer whales, subtidal communities. Some species “Not Recovering” >25 years later. | Impacts on local industries & communities. Settlement funds used for land protection. | Some species “Not Recovering” >25 years later. |

| ABT SUMMER | 1991 | 700 nautical miles off Angola | 260,000 | – | – | – |

| HAVEN | 1991 | Genoa, Italy | 144,000 | Effects still apparent 10 years after spill (genotoxic exposure in fish/shellfish). | Claimed $1,604M, compensated $178.97M. | Impacts apparent 10 years post-spill. |

| PRESTIGE | 2002 | Off Galicia, Spain | 63,000 | Contaminated vast coastline, reduced fish populations, persistent oil residues. | Impacted fisheries and marine life. | Long-term effects included reduced fish populations and persistent oil residues. |

| DEEPWATER HORIZON | 2010 | Gulf of Mexico, USA | 134 million gallons (507k tonnes) | Impacts on deep ocean corals (86% affected), failed oyster recruitment, damage to coastal wetlands, reduced dolphin/sea turtle/seabird populations. 800k coastal, 200k offshore birds died. Increased dolphin/sea turtle strandings, lung disease, reproductive failure in dolphins. | Potential losses of $3.7B total revenues, $1.9B profits, $1.2B wages, $8.7B economic impact (next 7 years). Fisheries most affected. | Recovery for some areas may take >20 years. |

| SANCHI | 2018 | Off Shanghai, China | 113,000 | – | – | – |

This table provides a concise overview of some of the most impactful oil spills, allowing for comparison of their scale, geographical reach, and the types of environmental and economic damage they caused. It also highlights the long-term nature of recovery, reinforcing the severity of these incidents.

Prevention, Response, and Technological Advancements

Significant regulatory frameworks and technological advancements have been developed to prevent and respond to oil and chemical spills, aiming to minimize their environmental and economic impacts.

In the United States, cornerstone legislation includes:

- The Clean Water Act (CWA), which prohibits oil discharges and mandates prevention and response plans,

- The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA), enacted after the Exxon Valdez spill, which strengthened the EPA’s ability to prevent and respond to catastrophic spills by requiring Facility Response Plans (FRPs) for high-risk facilities.

- The Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) Rule, part of the CWA, further mandates prevention plans including secondary containment, inspections, and operational controls.

- Worker safety during spill responses is addressed by OSHA’s Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER) standard, which sets guidelines for training, personal protective equipment (PPE), and safety procedures. Regular training and drills are essential to ensure preparedness and identify weaknesses in response plans. While these frameworks are robust, the persistence of smaller, illegal discharges suggests that continuous efforts in enforcement and compliance are needed.

Technological advancements have significantly transformed spill response capabilities.

- Autonomous systems, including unmanned surface vessels and underwater vehicles, are increasingly used for detecting and sampling oil plumes, enhancing safety, and enabling 24/7 response operations.

- Drones (unmanned aerial vehicles) provide crucial aerial surveillance, aiding initial assessments, tracking offshore oil slicks, and evaluating vessel damage, reducing health and safety risks for responders.

- Satellite systems offer global surveillance, enabling early detection of large-scale spills and monitoring drilling and transportation activities.

- Underwater sensors provide early leak detection and water quality monitoring.

- Radar image detection sensors provides real-time detection enabling faster response to cleaning activities.

- Improvements in traditional response equipment, such as skimmers and containment vessels, have enhanced their volume and recovery efficiency.

- Furthermore, new materials for oil cleanup and sophisticated software models, like NOAA’s GNOME model for spill trajectory forecasting, contribute to more effective response efforts.

- NOAA also provides comprehensive databases like the Chemical Aquatic Fate and Effects (CAFE) database for estimating the fate and effects of chemicals and oils.

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in the widespread and effective deployment of new technologies, including high costs, accessibility issues, data transparency and availability, maintenance and reliability concerns, data security, system integration complexities, and the need for qualified operators and updated regulations. This indicates that while technology exists to significantly improve spill response, its full potential can only be realized by combining these into a unified platform cable of detecting from the second is released until the spill is fully recovered as wall as investment in adaptive policy frameworks to enable the data transparency .

Time to Reframe the Narrative

We’ve made real progress. Oil spills no longer make daily headlines. But that doesn’t mean the danger has passed. It has simply changed shape.

Today, we face an ongoing crisis that blends technology, policy, and human behavior. We need stronger enforcement. Tighter regulations. And above all, a new mindset—one that treats the ocean not as an infinite resource to be used and forgotten, but as a living system whose health determines our own.

Whether it’s oil spilled offshore or chemicals discharged inland, the path of pollution always finds its way to the sea. It’s time for a “source-to-sea” strategy – a united, global approach to pollution prevention that sees the whole picture.

Because in the end, the sea remembers everything.

Leave a comment