Plastic Production Explosion

The proliferation of plastics since their mainstream adoption has led to an exponential increase in production, from 2 million tonnes per year in 1950 to an astonishing 460 million tonnes in 2019.

Waste footprint

In 2024, an estimated 220 million tonnes of plastic waste were projected to be generated globally. This averages out to 28 kg per person worldwide. Of this, approximately 69.5 million tonnes, or one-third, is expected to be mismanaged and end up in the natural environment.

Micro & Nano Treats

This surge has directly fueled a global pollution crisis, affecting aquatic and terrestrial environments from the polar regions to the highest mountains and deepest oceans. Within this broader context, microplastics (MPs), defined as particles between 0.1 and 5 mm, and nanoplastics (NPs), smaller than 1 µm, represent a severe and pervasive threat to all marine ecosystems and their inhabitants across all trophic levels.

Coral Reef Contamination

Microplastics have been consistently detected across all studied coral reefs, found within the water column, sediments, and even directly within coral organisms. A recent study conducted in the Gulf of Thailand, employing an innovative detection technique, revealed microplastics embedded in all three anatomical components of coral: the surface mucus (38%), tissue (25%), and skeleton (37%).

The concentrations of microplastics in coral reef systems vary geographically; for instance, in the Xisha Islands of the South China Sea, seawater concentrations ranged from 0.2 to 45.2 items per liter, while in Sanya Bay, Hainan Island, they were found between 15.50 and 22.14 items per liter. Within the corals themselves, abundance ranged from 1.0 to 44.0 items per individual in the Xisha Islands and 0.01 to 3.60 items per polyp in Sanya Bay.

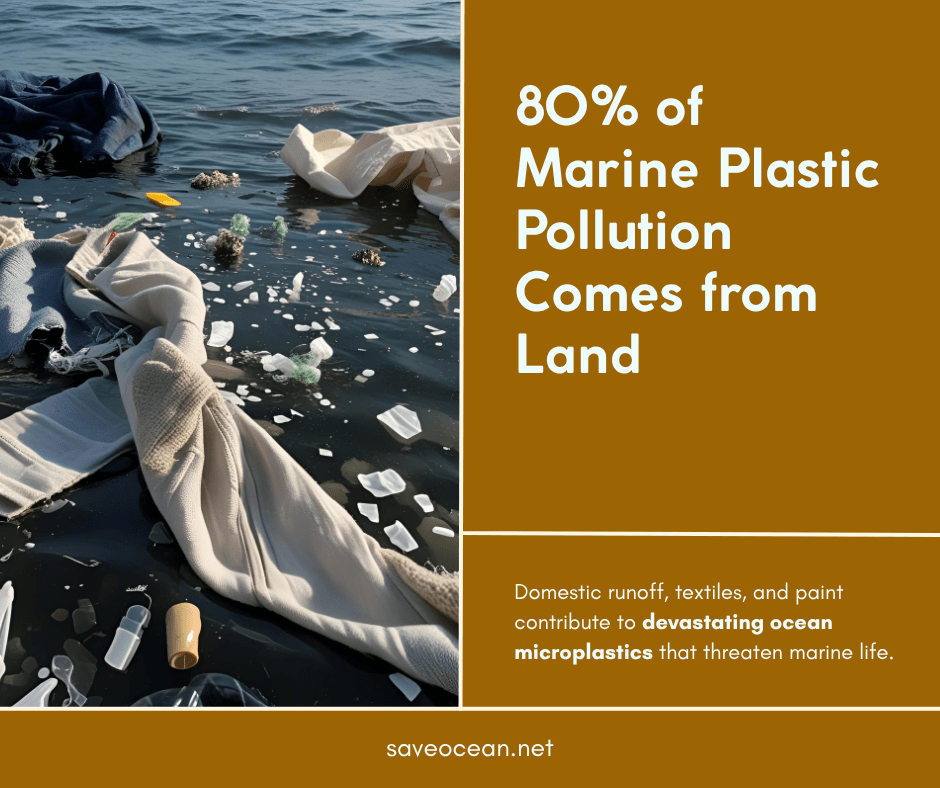

Where It All Comes From

80% land‑based → broken down into:

- 30% Other mismanaged plastics

- 35% Clothing fibers

- 10% Microbeads & fragments

- 5% Paint runoff

The primary origin of marine plastic pollution is overwhelmingly terrestrial, with approximately 80% attributed to inadequate land-based waste management practices

Specific contributors include domestic runoff containing microbeads and fragments from consumer products, the breakdown of larger plastic debris into secondary microplastics, and, significantly, the shedding of synthetic textile fibers like polyester, acrylic, and nylon during washing.

Textiles and clothing alone contribute an estimated 35% of all ocean microplastics, while paint is another substantial source, releasing an estimated 1.9 million tonnes annually.

Studies consistently show that fibrous microplastics are the predominant shape found in seawater, fish, and corals, with rayon and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) being common polymers. In the Gulf of Thailand study, nylon (20.11%), polyacetylene (14.37%), and PET (9.77%) were the most prevalent types identified in coral samples.

In Sanya Bay, Hainan Island, microplastics smaller than 2mm and fiber types were predominant in both seawater and corals. This prevalence of fibrous microplastics strongly implicates the textile industry and everyday laundry practices as significant contributors to coral degradation.

Future Projections

Projections indicate that the 19–23 million metric tons of plastic waste that entered aquatic ecosystems in 2016 could surge to 53 million metric tons by 2030, even with diligent mitigation efforts.

Despite the widespread nature of this issue, current comprehensive spatial coverage of microplastic studies in coral reefs remains limited, with fewer than 30 field studies analyzed globally, underscoring a critical gap in understanding the full extent of the problem.

The pervasive presence of microplastics across all components of coral reef ecosystems, including water, sediment, and the very anatomy of corals, highlights a profound and growing contamination. The continuous cycling of plastics within the reef environment means that even if new plastic inputs were to cease, existing plastics would continue to degrade into smaller, more hazardous particles, presenting a long-term, compounding challenge.

This scenario portrays a silent, creeping crisis where the problem is not merely widespread but also intensifying and becoming increasingly integrated within marine life, necessitating sustained interventions beyond just preventing new pollution.

How Microplastics Compromise Coral Health

The mechanisms through which microplastics inflict harm on coral reefs are multifaceted, encompassing physical, chemical, and biological pathways that collectively undermine coral health and ecosystem resilience.

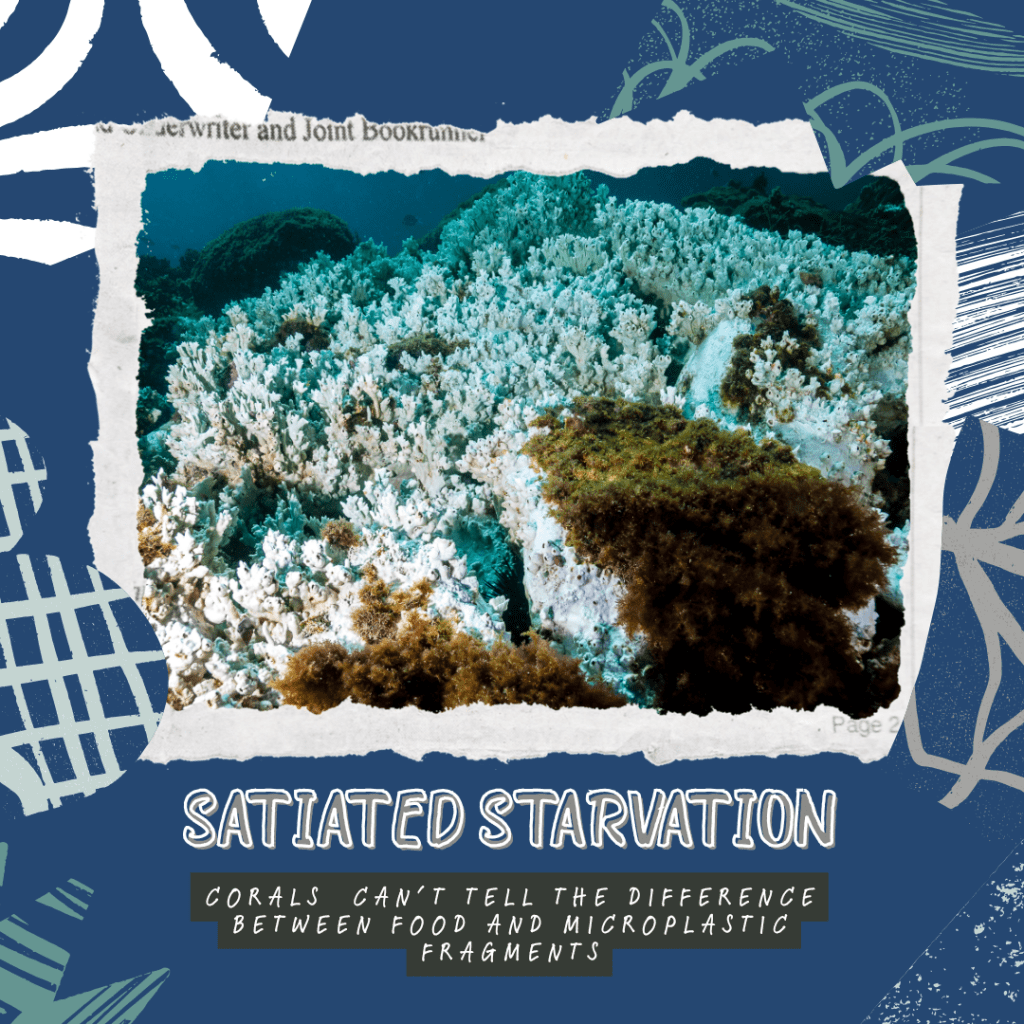

Satiated Starvation

Corals, as suspension feeders, naturally extend their tentacles to capture tiny food particles like zooplankton floating in the water. However, microplastics, often similar in size and shape to these food items, can be mistakenly ingested by corals, either directly or indirectly through trophic transfer.

Corals feed by filtering tiny prey from the water—yet they can’t tell the difference between food and microplastic fragments. When they swallow these indigestible bits, their stomachs “feel” full, leading to a false sensation of fullness but no nutrients arrive. Day after day, the reef’s architects literally starve while looking healthy on the surface—a cruel deception that leaves entire colonies weakened from within leading to a slow, insidious death by malnutrition.

Physical trauma

Beyond ingestion, larger plastic debris can inflict direct physical trauma, such as entanglement in fishing lines or being covered by plastic bags, causing tissue damage, and potentially leading to the coral’s weakening or death.

Microplastics can also adhere to coral surfaces at rates 3.9 times higher than ingestion, with fibers being the predominant type for both processes. While corals possess defense mechanisms like mucus production, ciliary movements, and tissue contraction to remove foreign particles, these processes are energetically costly when dealing with persistent microplastic exposure.

Invisible Skeleton Saboteurs

Perhaps most alarmingly, microplastics can become permanently incorporated into the aragonitic skeletal structure of corals. As corals grow, they can trap microplastics inside their calcium‑carbonate skeletons.

The long-term consequences of such inclusions on skeletal properties, including stability and hardness, are still under investigation but represent a significant concern. Compromised skeletal integrity has profound ripple effects for the entire reef ecosystem, as it diminishes the quality of habitat and protection for countless marine species that depend on the reef’s complex three-dimensional structure.

This permanent embedding is a grim “time capsule” of human waste: centuries from now, dead reefs will still be laced with our plastics, their once‑sturdy skeletons weakened, unable to support fish nurseries, sea turtles, or the million species that need them.

Chemical Toxicity

Plastics are not inert; they are manufactured with various chemical additives and can readily adsorb harmful pollutants from the surrounding seawater, including flame retardants, heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and persistent organic pollutants (POPs).

When corals ingest microplastics, these toxins can leach into their internal systems, causing significant disruption. This includes impairing their immune functions and interfering with the vital symbiotic relationship between corals and their zooxanthellae algae, which are crucial for the coral’s energy production and vibrant coloration.

This significantly amplifies their destructive potential, making the problem multi-layered and far more challenging to combat. It emphasizing the hidden and compounding dangers that extend beyond visible plastic debris.

Biological Vectoring: The “Plastisphere” and its Role in Disease Transmission

Microplastics provide an ideal surface for microbial colonization, leading to the formation of distinct biofilms known as the “plastisphere”. This plastisphere can alter biogeochemical processes within the marine environment and, critically, act as a vector for invasive species and potential coral pathogens.

The presence of plastic pollution dramatically increases the vulnerability of coral reefs to disease; studies have shown that the risk of disease can escalate by up to 22 times on plastic-polluted reefs compared to pristine ones. Larger plastic debris has also been implicated in disease transmission.

The alarming statistic of a 22-fold increase in disease risk underscores the severity of this biological vectoring. This leads to a broader ripple effect: increased disease outbreaks weaken corals, making them more susceptible to other environmental stressors, ultimately destabilizing the entire reef ecosystem and leading to a decline in biodiversity and overall resilience.

Physiological Stress: Reduced Growth, Impaired Feeding, and Altered Photosynthetic Performance Leading to Bleaching

Exposure to microplastics elicits a range of physiological stress responses in corals. These include increased mucus production, reduced feeding rates, compromised immune systems, and alterations in photosynthetic performance, which can ultimately lead to coral bleaching and tissue necrosis. For example, microplastic fibers (but not spheres) were observed to reduce the photosynthetic capability of Acropora sp. by 41% at ambient temperatures over a mere 12-day period.

The ingestion of microplastics can trigger an immune reaction in corals, akin to responses seen in mammals, resulting in a persistent state of inflammation and irritation. The energetic cost associated with handling microplastics—including their capture, ingestion, and subsequent egestion—significantly depletes the coral’s energy budget. This depletion negatively impacts the coral’s overall health, growth, and reproductive success.

Alarmingly, corals already under stress, such as those experiencing bleaching, have been found to ingest more microplastics than natural food sources. This creates a detrimental feedback loop, exacerbating their vulnerability and increasing the likelihood of mortality, as microplastics provide no nutritional value to the energy-depleted corals.

This depletion makes corals significantly less resilient and more susceptible to other major environmental stressors, particularly those related to climate change like thermal bleaching and ocean acidification.

Corals as “Sinks”: Explaining the Missing Plastic Problem

A significant scientific hypothesis proposes that corals may serve as a substantial “sink” for microplastics by actively absorbing them from the ocean. This mechanism offers a potential explanation for the long-standing “missing plastic problem,” which refers to the approximately 70% of plastic litter that is believed to have entered the world’s oceans but remains unaccounted for.

The absorbed microplastics are not merely stored superficially; they become integrated and embedded within the coral’s skeletal structure. A particularly unsettling implication is that because coral skeletons can endure for hundreds of years after the coral’s demise, these deposited microplastics could be preserved within them for extended periods, drawing a chilling parallel to “mosquitos in amber”. This function positions coral reefs not just as victims of pollution but as critical accumulation zones for microplastics, making them important areas for understanding the global plastic budget.

It means that coral reefs are not merely suffering from plastic pollution; they are actively becoming repositories of human waste, forming a geological archive of the Anthropocene’s plastic footprint. The “amber” analogy vividly conveys a grim reality: even if all new plastic inputs ceased today, the existing microplastics embedded within the reefs would continue to pose a long-term, potentially delayed threat as they could be released back into the environment over centuries. This transforms the vibrant, living reef into a toxic time capsule, underscoring the intergenerational and enduring impact of plastic pollution, and suggesting that the problem will persist long after its immediate sources are addressed.

Compounding Stressors and Critical Knowledge Gaps

Despite the growing body of evidence detailing the harm caused by microplastics, comprehensive studies examining the synergistic interactions between microplastic exposure and other major anthropogenic stressors, such as ocean acidification and rising temperatures, remain limited. This represents a critical area for research, particularly given existing evidence that thermal bleaching, a direct consequence of rising ocean temperatures, can exacerbate microplastic impacts. Bleached corals have been observed to ingest more microplastics and retain them for longer durations, leading to greater internal exposure and amplified harm.

The full extent of microplastic pollution’s impact on corals necessitates further investigation. A significant knowledge gap persists regarding the levels and effects of nanoplastics (NPs), primarily due to limitations in current detection techniques. This is particularly concerning as nanoplastics are hypothesized to pose the greatest risk due to their ability to translocate into different organs and across cell membranes. To facilitate effective decision-making for ecosystem protection, the development of standardized methods for assessing both microplastics and nanoplastics is essential. Furthermore, the precise mechanisms through which microplastics exert their negative impacts on corals are not yet fully elucidated. More research is needed to identify which specific characteristics of microplastics—such as size, morphology, polymer type, and associated chemicals and microbes—are responsible for eliciting these impacts. Future research must prioritize environmentally relevant microplastic types, concentrations, and exposure periods to ensure that findings accurately reflect real-world conditions. This paints a grim picture of a “perfect storm” where microplastic pollution does not act in isolation but actively exacerbates the already devastating effects of climate change on coral reefs. This complex interplay creates a more resilient and multi-faceted threat that is harder to predict and mitigate. The lack of understanding regarding these combined stressors and the insidious nature of nanoplastics (which are harder to detect but potentially more dangerous) underscores an urgent need for accelerated, standardized, and interdisciplinary scientific research. This implies that current conservation interventions might be insufficient without a clearer, holistic picture of these compounding threats, highlighting the critical role of scientific advancement and international collaboration in effective reef protection.

Call for Action

The data establishes a clear and direct causal link:

- human consumption patterns and

- insufficient waste management practices on land

are the primary drivers of microplastic contamination in coral reefs.

This implies that effective solutions must fundamentally address land-based sources and consumer behavior, rather than solely focusing on ocean cleanup efforts, emphasizing the need for systemic change.

This understanding provides a clear, actionable target for both consumer behavior change:

- Choosing natural fibers,

- Promoting sustainable textile production,

- Developing washing machine filters.

For organizations focused on ocean conservation, this means campaigns can move beyond generic anti-plastic messages to focus on specific, high-impact sources like clothing, making the problem more tangible and the solutions more direct for individuals.

Works cited

- Microplastics: impacts on corals and other reef organisms – PMC – PubMed Central, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9023018/

- Microplastics: impacts on corals and other reef organisms, https://research.esr.cri.nz/articles/journal_contribution/Microplastics_impacts_on_corals_and_other_reef_organisms/22223920

- Microplastics in the Coral Reef Systems from Xisha Islands of South China Sea | Environmental Science & Technology – ACS Publications,https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.est.9b01452

- Abundance and Characteristics of Microplastics in Seawater and Corals From Reef Region of Sanya Bay, China – Frontiers, accessed https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.728745/full

- Coral Reefs Found to Absorb Microplastics – Technology Networks https://www.technologynetworks.com/applied-sciences/news/coral-reefs-found-to-absorb-microplastics-391227

- Microplastics found in coral skeletons – ScienceDaily, accessed https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/09/240920112714.htm

- Microplastics Found Lurking Inside Coral Skeletons – Newsweek, https://www.newsweek.com/microplastic-pollution-coral-reef-skeletons-plastic-waste-marine-life-1957956

- Effects of Plastic Pollution on Coral Reefs [2025] – SWOP – Shop …, https://www.shop-without-plastic.com/blogs/plastic-pollution-awareness/effects-of-plastic-pollution-on-coral-reefs

- Microplastics in our oceans and marine health – OpenEdition Journals, https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/5257

- Microplastics – Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microplastics

- The Invisible Threat: How Microplastics Endanger Corals – Frontiers for Young Minds, https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2021.574637

- (PDF) Exploring Microplastic Interactions with Reef-Building Corals Across Flow Conditions, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383071774_Exploring_Microplastic_Interactions_with_Reef-Building_Corals_Across_Flow_Conditions

- (PDF) Microplastics: Impacts on corals and other reef organisms – ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358479567_Microplastics_Impacts_on_corals_and_other_reef_organisms/download

- Predicting microplastic dynamics in coral reefs: presence, distribution, and bioavailability through field data and numerical simulation analysis – PMC – PubMed Central, accessed July 21, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11991954/

- Microplastic ingestion by coral as a function of the interaction between calyx and microplastic size – PMC – PubMed Central, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8788577/

- Impacts of microplastics on growth and health of hermatypic corals . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335238335_Impacts_of_microplastics_on_growth_and_health_of_hermatypic_corals_are_species-specific

- Reef-Building Corals Do Not Develop Adaptive Mechanisms to Better Cope With Microplastics – Frontiers, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/marine-science/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.863187/full

- Scleractinian corals incorporate microplastic particles: identification from a laboratory study, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8302493/

- Plastisphere: Marine Microbial Assemblages for Biodegradation of Microplastics | Request PDF – ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380559688_Plastisphere_Marine_Microbial_Assemblages_for_Biodegradation_of_Microplastics

- Species-specific impact of microplastics on coral physiology – University of Edinburgh Research Explorer, https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/files/186438989/614._Hennige.pdf

- It’s a Plastic World: The Emerging Threat to Reef-Building Corals – Diving Deeper – University of Miami, https://rescueareef.earth.miami.edu/media/diving-deeper/its-a-plastic-world-the-emerging-threat-to-reef-building-corals/index.html

Leave a comment