By late afternoon the beach was breathing—slow, foamy exhalations on a September tide. A boy ran ahead of his mother, chasing something he’d never seen before: fist-sized, straw-brown spheres with wiry fibers, like tiny tumbleweeds left by a wandering desert. He picked one up and froze. In the tight weave of the ball, a blue shard of plastic winked in the sun.

The ocean had brought us a message, rolled up in seagrass and grit.

These are Neptune balls: dense bundles spun by Posidonia oceanica, the ancient seagrass that tapestries the Mediterranean seabed. In storm seasons, the plant’s tough leaf fibers tangle into ovals and spheres—aegagropilae—and sometimes, they carry what we’ve thrown away. Scientists examining beached Neptune balls on Mallorca found plastics in 17% of the balls, with up to 1,470 plastic items per kilogram of plant material; loose piles of dead leaves (wrack) held plastics in 50% of samples, up to 613 items per kilogram. The polymers weren’t just floating fragments; many were the denser, sink-prone plastics (like PET and nylon) that seagrass canopies slow and trap on the seafloor—until waves roll them back to us.

It’s tempting to call this a miracle cleanup. It isn’t. It’s a reckoning. Seagrass meadows—places that buffer coasts, shelter young fish, and lock away carbon—are simply doing what living systems do: changing water flow, catching particles, knitting the loose ends of the sea into something that holds. In that weave, this century’s habits show up as bottle flakes, filament from fishing line, and the off-white ellipses of pre-production pellets we blandly call nurdles.

Echoes from other shores

Our story doesn’t end with one beach.

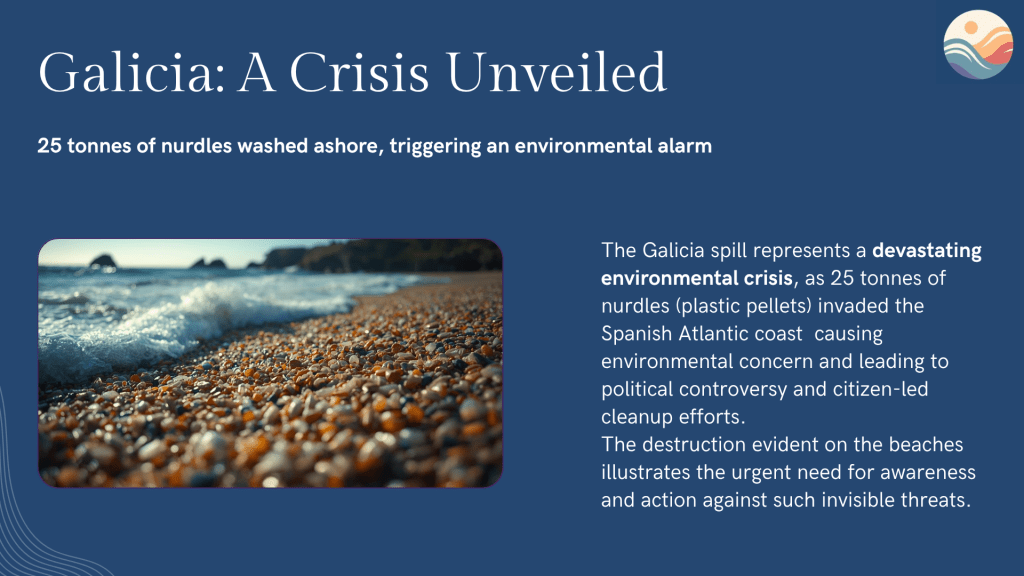

- Galicia, Spain (2023–2024): After a cargo loss off Portugal, millions of nurdles—about 25 tonnes—washed onto the Spanish Atlantic coast, forcing emergency cleanups and a criminal probe. The pellets were small enough to sift through fingers, numerous enough to paint entire coves.

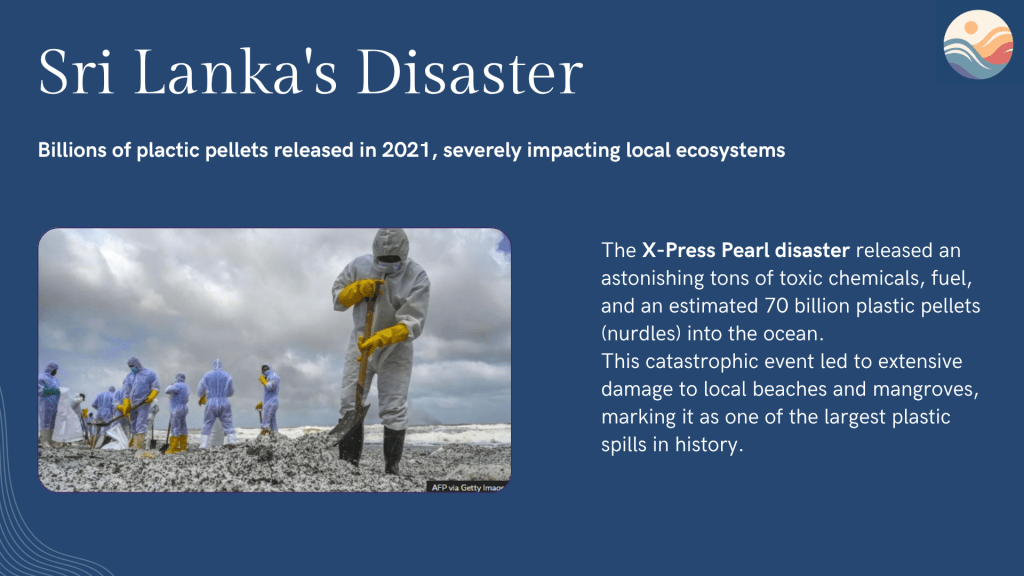

- Sri Lanka (2021): When the container ship X-Press Pearl burned and sank near Colombo, roughly 1,680 tonnes of nurdles spilled—a blizzard of white beads buried into beaches and mangroves, mixed with char, chemicals, and grief. Researchers call it one of the largest plastic pellet spills ever recorded.

- Open ocean to the poles: Microplastics ride wind as well as water. They’ve been found in Antarctic snow—a place we once believed too far, too cold to touch. Every “away” we throw to is somebody’s “here.”

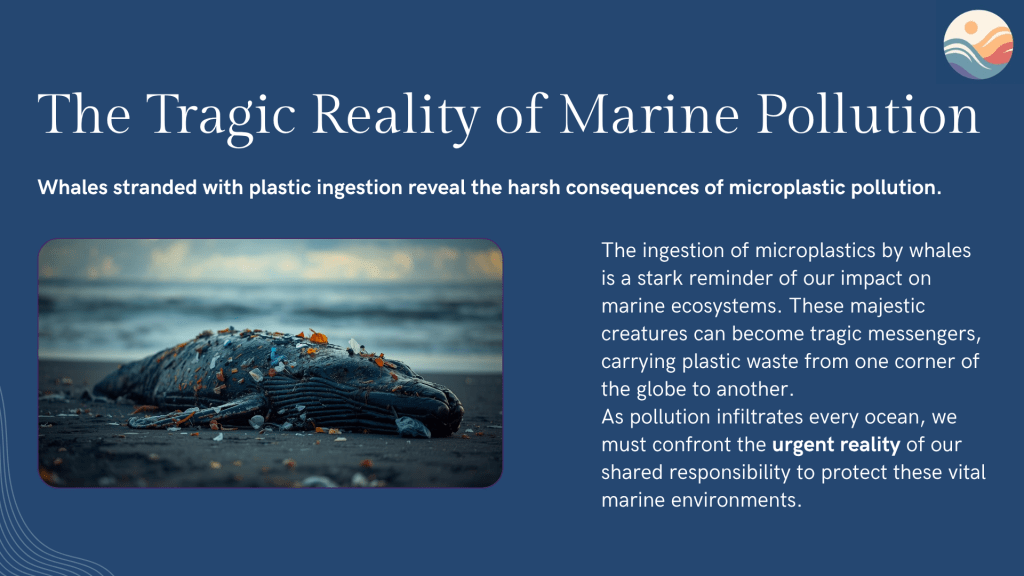

- The animals who carried our proof: In Indonesia and the Philippines, whales have stranded with kilograms of plastic in their bellies—bags, cups, rope, flip-flops—the detritus of daily life compacted into a fatal hunger. These are not statistics; they are autopsies.

Each scene is different. The plot is the same.

What the Neptune balls are really saying

The science is clear: seagrass meadows slow currents, trap particles, and sometimes bind plastics into durable balls that storms then eject onto beaches. It’s a natural purge mechanism—a reminder that the seafloor is a major sink for plastics and that part of that load can be rolled back to shore bundled inside living architecture. But this is not a cleanup strategy; removing wrack and Neptune balls wholesale can damage beaches and dunes that rely on that organic armor. The wiser move is to protect the meadows and turn off the tap of plastic upstream.

A SaveOcean pledge, written in tide lines

SaveOcean is not a logo. It’s a promise we make aloud where the waves can hear us.

- Map, restore, and enforce protections for Posidonia and other seagrasses. Their meadows are nurseries, carbon banks, and—whether we deserve it or not—our inadvertent filters.

- Mandate closed-loop handling, real-time spill reporting, and zero-loss standards for nurdles from factory to ship to port. We’ve seen what “just pellets” look like on a beach.

- Ban the most litter-prone formats, require tethered caps and true recyclability, and price virgin resin so reuse finally wins.

- Stormwater filters, textile fiber capture, and port skimmer programs keep microplastics out of the surge that feeds wrack lines.

- When Neptune balls and wrack wash ashore, leave them where practical. They stabilize beaches and feed dune life. If we have to remove them in tourist zones, do it gently—and mind the plastic inside.

The ending we can write

At dusk the boy placed the sphere back in the wet sand, more careful now. The tide took its measure of the day, and the ball settled among a scatter of others—small round testaments to a meadow we cannot see from shore and rarely think about.

The ocean is not handing us a solution; it is handing us the evidence.

Let’s answer with more than shame. Let’s defend the meadows that stitched this message. Let’s stop the spills that seed the next one. And let’s make the beach a place where a child can run without learning, too early, how much of us the sea has had to carry.

Sources for the facts in this story

- Scientific Reports (2021): Field study of Posidonia wrack and Neptune balls in Mallorca; plastics in 17% of balls (up to 1,470 items/kg) and in 50% of wrack (up to 613 items/kg); mechanism of trapping and beaching. Nature

- Galicia nurdle spill (2023–2024): Peer-reviewed case report and major news coverage documenting ~25 t of pellets along ~1,500 km of coastline. sciencedirect.com+2theguardian.com+2

- Sri Lanka X-Press Pearl (2021): Peer-reviewed analysis and response summaries reporting ~1,680 t of nurdles released. pubs.acs.org+2pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov+2

- Polar microplastics: First evidence of microplastics in Antarctic snow (2022) and subsequent studies of remote Antarctic sites. tc.copernicus.org+1

- Whales and plastics: Documented strandings with large plastic loads (2018–2019). National Geographic+1

Leave a comment