The concept of the Blue Economy, defined as the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and ocean ecosystem health, has evolved significantly characterized by a critical shift: moving from merely recognizing the ocean’s economic potential to prioritizing its resilience, equity, and digitalization.

The challenge is to ensure that economic growth does not undermine the foundational ecological assets upon which it depends. Recent advancements show that the most successful strategies balance large-scale investment in “blue technology” with localized, nature-based, and community-driven governance.

The Digital Ocean

A central theme in the last years Blue Economy landscape is the integration of advanced technology to improve monitoring and enforcement, creating what are often termed Smart Marine Protected Areas (SMPAs).

Traditional monitoring of vast marine areas often proved ineffective, especially in developing regions. The period 2020–2025 saw the accelerated deployment of digital tools to bridge this gap:

Autonomous Monitoring: AI-driven autonomous vessels (AUVs/USVs) for large-scale, real-time data collection, enhancing environmental assessment and maritime security.

Satellite-Based Enforcement: Technologies leveraging public data, such as the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission, combined with Human-Assisted Machine Learning, allow for cost-effective, up-to-date habitat mapping (e.g., mangroves and seagrass) and identification of illegal activities like fishing. This remote sensing technology empowers local stakeholders with scientific baselines, which is a significant step beyond the data deficiency issues noted in conservation efforts like those in Cambodia.

Predictive AI: The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for predictive modeling helps managers dynamically adjust conservation boundaries or enforcement priorities in response to real-time ecological changes, such as species migration or climate impacts.

Europe’s Digital Twin of the Ocean (DTO) moved from concept to operational core infrastructure (EDITO), offering data/model toolboxes and “local twins” for mapping illegal fishing risk and habitat suitability to target enforcement, optimizing marine sanitation capex and tracking pollutant load reductions, and pollution control.

Why it matters:

While these advancements offer transformative potential for global ocean governance, the new Frontiers study from Cambodia’s Kep Marine Fisheries Management Area (MFMA) shows that fisheries productivity structures (FPSs) can both deter illegal bottom trawling and support early signs of seagrass recovery highlighting the crucial need for context-appropriate technology.

Investing in Blue Resilience

Between 2020 and 2025, investment in the Blue Economy shifted to focus heavily on sectors that actively contribute to climate adaptation and resilience.

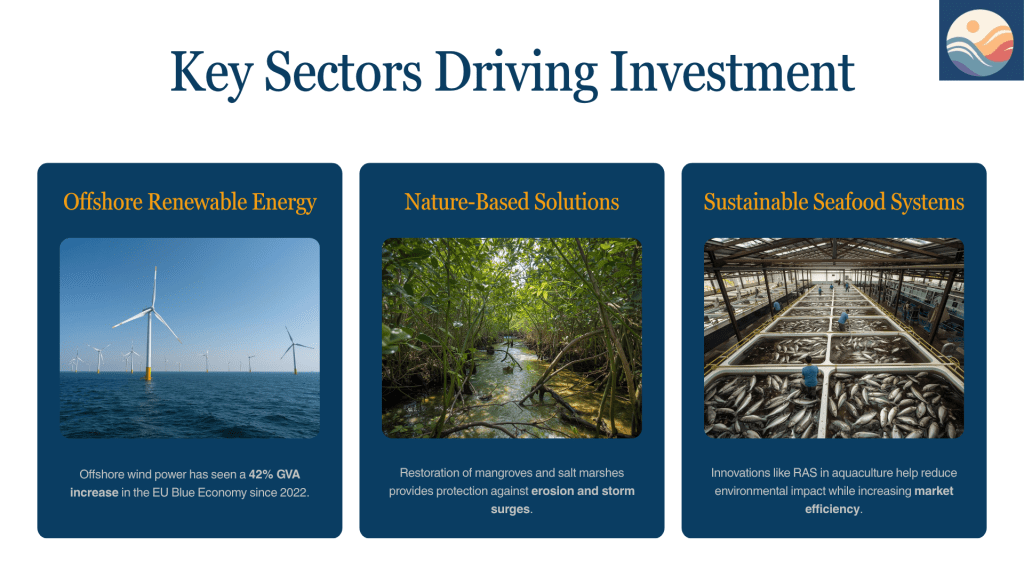

The Offshore Renewable Energy sector, particularly wind, saw massive growth, becoming one of the fastest-growing segments of the EU Blue Economy (42% GVA increase in 2022). However, complementary investments in Nature-Based Solutions (NbS) gained significant traction as a key resilience strategy:

Coastal Protection: NbS, such as the restoration of mangrove forests, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows, is increasingly recognized for its climate benefits, with benefits estimated to outweigh costs by a factor of 3.5. These ecosystems provide vital protection against coastal erosion, storm surges, and sea-level rise.

Blue Carbon Finance: Global frameworks and financing vehicles, including guidelines for “Debt-for-nature” Blue Bonds, have emerged to scale up investment in coastal blue carbon ecosystems, which are critical carbon sinks. For example: Belize (2021): USD 364m debt conversion → ~12% of GDP debt reduction and ~USD 180m for ocean conservation; commitments to protect 30% of waters. Barbados (2022–2024): USD 150m blue bond/debt swap; ~USD 50m savings over 15 years for marine protection; follow-on debt-for-climate swap to upgrade wastewater systems and cut marine pollution.

Sustainable Seafood Systems: To meet the escalating global demand for protein, the Marine Fisheries & Aquaculture segment remains a dominant market force. Innovation here centers on sustainability, with systems like Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) and selective breeding improving efficiency and reducing the environmental footprint compared to traditional methods.

Common guidance: UNEP FI’s Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles and toolkits (incl. 2025 Ocean Investment Protocol) plus OECD mapping of blue taxonomies; IFC’s Blue Finance Guidelines v2.0 (2025) gives banks concrete use-of-proceeds screens.

Development banks scaling up: CAF doubled blue-economy investments to USD 2.5bn by 2030, signaling growing public capital.

Why it matters:

The protection and restoration of habitats, as advocated by the study on Cambodia, now have a clear global economic rationale linked to both climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, attracting public and private finance.

The investment community now has clearer do-no-harm filters, vital for moving from one-off swaps to pipelines that fund habitat restoration, marine sanitation, and coastal resilience at scale.

The Equity Blue Economy Imperative

A core policy focus from the UNDP, World Bank, and G20 during this period has been the necessity of an equitable Blue Economy, recognizing the disproportionate impact of climate change and environmental degradation on coastal communities and small-scale fishers.

Centering Livelihoods: International policy frameworks now emphasize that small-scale fisheries and aquaculture are central to a sustainable and equitable Blue Economy, providing food security and livelihoods to millions. This requires a bottom-up approach that integrates local knowledge.

Community-Led Governance: Research validates that the engagement of local communities in decision-making leads to conservation initiatives that are more reflective of socio-economic conditions, promoting compliance and long-term sustainability. Models like Local Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs), often supported by grassroots efforts similar to those establishing the Kep Marine Fisheries Management Area (MFMA) in Cambodia, have proven effective.

Policy Integration: There is a strong push to move beyond fragmented governance towards unified and coordinated policy frameworks. These frameworks must align national economic plans (like India’s Blue Revolution and Deep Ocean Mission) with global sustainability goals, while ensuring the equitable distribution of costs and benefits.

The Blue Food Assessment highlighted aquatic foods’ outsized role in nutrition and livelihoods with generally lower land and water footprints than many terrestrial meats—if managed well. This supports targeted investments in small-scale fisheries, aquaculture modernization, and wastewater upgrades that cut eutrophication and disease risk.

Why it matters

Development efforts are now focused on building local capacity to establish integrated ocean policies and access new financial instruments.

Governance breakthroughs

The Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) locked in Target 3 (“30×30”), protect 30% of land and sea by 2030, orienting national marine planning and finance. Progress is uneven, but it’s the first shared north star for “nature-positive” ocean action.

In September 2025, the BBNJ/High Seas Treaty cleared the 60-ratification threshold; it enters into force January 17, 2026. Expect new high-seas MPAs and rules on environmental impact assessments—key for shipping lanes, deep-sea mining, and migratory stocks.

So what? Policy certainty de-risks investment. Coastal states can align blue finance with legal protection and access new global tools for areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Where to go next (2026 horizon)

Scale “conservation infrastructure” like FPSs, living shorelines, and wastewater retrofits using blue-bond structures linked to GBF targets.

Deploy DTO-powered local twins for each financed project to publish open MRV on ecological and economic returns.

Use development banks’ new envelopes and OECD guidance to crowd in private capital, prioritizing community-led fisheries and pollution control.

Key Takeaway

In conclusion, the advancements from 2020 to 2025 reveal that a resilient Blue Economy is not simply a matter of economic output; it is an integrated socio-ecological system. Future success hinges on the fusion of cutting-edge digital technologies for data and enforcement with nature-based solutions and the equitable empowerment of the coastal communities whose stewardship is the most effective bulwark against habitat loss.

Sources of information

- Ho et al. 2025. Strengthening a blue economy after habitat loss (Cambodia; anti-trawling structures & seagrass recovery). Frontiers in Marine Science. Frontiers

- UN CBD: Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework & Target 3 (30×30). Convention on Biological Diversity

- High Seas Treaty (BBNJ): reached 60 ratifications (entry into force Jan 17, 2026). High Seas Alliance

- UNEP FI: Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles; Ocean Investment Protocol (2025). unepfi.org

- OECD (2025): guidance and taxonomy overview for sustainable ocean economies. OECD

- IFC (2025): Guidelines for Blue Finance v2.0. IFC

- Blue bonds: Belize (2021) & Barbados (2022–2024) case studies and outcomes. nature.org

- Blue foods: Blue Food Assessment; Nature syntheses on nutrition & sustainability. BFFP

- Digital Twin of the Ocean: EU DTO/EDITO program documentation. Research and innovation

- Offshore wind trendlines: GWEC/WFO/IEA/IRENA updates through 2024–2025. WFO-Global

- Ocean climate solutions & mCDR evidence: Ocean Panel 2023 update; Gattuso et al. syntheses; seaweed CDR MRV reviews. oceanpanel

Leave a comment